Wilfrid Edward Cooper was born on 22 May 1926 in Observatory, a suburb of Cape Town, Cape Province (now Western Cape Province) and lived in Mowbray until he finished his schooling. His mother, Rose Emma, was born in Cornwall, England and his father, Victor, in Woodstock, Cape Town. They were married in 1923. His father was an engine driver with the railways as was his grandfather, Henry, who had been one of the drivers who had driven the train which took the body of Cecil John Rhodes to be buried in the Matopos in the then Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

His father became an engine driver in October 1926 and in 1933 was promoted to first class engine driver and was transferred to the small town of Klawer on the banks of the Oliphant’s River in Namaqualand. While in Klawer his sister, Nancy, was born in November 1930.

From 1933 at age six and a half he attended the local Afrikaans medium school in Klawer. At the end of October 1935 his father was transferred to Malmesbury, Cape Province. Here he attended Die Hoer Jongenskool [1] from standards 1 (now grade 3) to 6 (now grade 8) until 1940. In 1941 he moved to Cape Town where he then attended Wynberg Boys High. Here he passed his Junior Certificate in 1943 and a first class Senior Certificate in 1944. A badly broken arm in a rugby match early in his playing career ended his playing the sport but he continued to participate in cricket, representing the school in athletics in 1943 and 1944. In 1944, he won the open mile in the school’s annual athletics competition at Newlands cricket ground.

In 1945 he enrolled at Stellenbosch University for his BA (Law) degree. Whilst living in Klawer and Malmesbury he learned to speak Afrikaans but as all lectures at that time were in Afrikaans, and by studying Hollands 1, he became fluent in the language and developed a great love for it. As many trials at the time were conducted in Afrikaans his fluency in the language was a great advantage to him in later years when appearing in court. In October 1945 with the assistance of the University of Cape Town National Union of South Africa Students (NUSAS) executive members and in the face of opposition from the Stellenbosch SRC he embarked upon establishing a branch of NUSAS with 26 students, mainly English speaking. He played an active role in NUSAS until the end of his student career and was Vice-President, National Secretary for Economics and Politics in 1945 and 46, and National Director of Research and Studies, from 1946 until 1947.

On 22 October 1949, Wilfrid Cooper married Gertrude Hope Posthumus who was not only to be his wife but his confidante, mentor and critic for the next fifty-five years. They set up home in the late 1950s in Palmboom Road, Newlands, Cape Town and lived there for over forty years. Their home was at the end of a small, unnamed lane next to that of the parents of Richard (Dick) Dudley who they got to know. In 1961 in terms of the Group Areas Act the Dudley’s were forced to move and in later years Gertrude would lock horns with the Cape Town City Council to have, after a long struggle, the lane named Dudley Lane in honour of the Dudley family.

He graduated from Stellenbosch in December 1947 and enrolled as a part-time LLB student with the University of South Africa (Unisa) and was appointed as a temporary messenger in the senate for a few months. Thereafter he took a position as a registrar at the Supreme Court in Cape Town and was registrar for two years for the legendary Judge Joseph Herbstein. He also worked under Judge G G Sutton when Judge Herbstein was on sabbatical.

From January 1951 he was a Clerical Assistant Grade II at Wynberg Magistrates Court until he attained his LLB degree in August 1952 and was called to the Cape Bar on 3 October of that year.

Given his fluency in Afrikaans, and in order to have an additional income, in 1954 he took a position as a part-time translator in the Senate where the proceedings were recorded in Hansard in the official languages of the day, English and Afrikaans. His position resulted in him translating many of the Afrikaans speeches of Dr Hendrick Verwoerd, then a senator, but who would later be Prime Minister of South Africa in September 1958.

He took silk (was appointed Senior Council) at the Cape Bar in April 1965.

In 1964 when appearing as Advocate Cooper’s junior in the trial of Stephanie Kemp, Albie Sacks wrote the following in his book “Stephanie on Trial” :

“The leader of the team responsible for Alan and Stephanie’s defence was Wilfred (sic), a lithe, ambitious advocate regarded as one of the leading trial lawyers at the Cape Bar. Before starting to practice he had been a public prosecutor and had developed a fierce cross-examining style which had led many of his colleagues to call him by the nickname “Tiger”. His court manner had lost none of its attack, and his lively temperament, which he always harnessed fully to his client’s cause, drew many people to watch him in action. Yet the main bases of his successes was less spectacular: the fanatical thoroughness with which he always prepared his cases and his flair for adjusting rapidly and sensibly to the shifting fortunes of trial. His appearance was strikingly youthful, but he had a penetrating caustic voice and verbal facility of a much older man. The wide interests of his earlier years- he was now approaching forty-had given way to a passion to be a respected advocate, and one day possibly, a judge. The pending sabotage trial threatened to raise many tricky issues for the defence, but if well handled could materially enhance counsel’s reputation. Many of our colleagues would have found a way out of accepting such a brief, but Himie ( sic Bernardt) was confident that even if he disagreed profoundly with their views, Wilfred would do wholehearted and intelligent battle for his clients.”

Wilf, as he was known to his friends and colleagues, was also an academic of note, having lectured on evidence in the mid 1950s at the University of Cape Town and in the 1960s and 1970s in Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure, Criminal Procedure and Civil Procedure and Roman-Dutch Law. In the 1970s and 1980s he also acted as an external examiner for various subjects. He obtained two doctorates; first, a PhD in 1972 from the University of Cape Town for the thesis entitled “The Letting and Hiring of Immovable Property in South Africa”. Then a LLD in 1987 from the University of Cape Town for his work Motor Law which was a complete revision of his original work, South African Motor Law, published in 1965. Over a period of forty years he published a number of books.

1955 Handbook on the Criminal Procedure Act (co-author B R Bamford)

1965 South African Motor Law (co-author B R Bamford)

1967 South Africa Road Traffic Legislation

1973 The South African Law of Land Lord and Tenant

1975 South African Motor Law 2nd Edition (co-author B R Bamford)

1977 The Rent Control Act (supplement to Land Lord and Tenant)

1979 Alcohol, Drugs and Road Traffic (co-authors Schwarr and Smith)

1982 Motor Law Volume 1 – Criminal Liability

1985 Road Transport – commentary on and text of the Road Transport Act

And Regulations

1987 Motor Law Volume 2 – Principles of Liability

1990 Road Traffic Legislation = Padverkeerwetgewing

1994 Landlord and Tenant 2nd Edition

1996 Delictual Liability in Motor Law

He was considered an authority on South African road traffic legislation.

In continuing the legacy which Cooper established in his writing, in 2008 leading academic and chair in law at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Pietermaritzburg since 2002, Prof Shannon Hoctor published “Cooper’s Motor Law: criminal liability, administrative adjudication & medico-legal aspects”.

In his 37 years as an advocate he handled cases not only in Cape Town but in all the major centres, neighbouring states as well as in many of the smaller towns across the length and breadth of South Africa. Some of the more notable trials which he acted in were:

1961 Marthinus Rossouw for the murder of Baron Dieter Von Schauroth

1964 Stephanie Kemp, Alan Brookes and Anthony Trew for Sabotage

1966 Demetrio Tsafendas for the assassination of Dr H F Verwoerd

1972 Robert Kemp for delivering a public address near St Georges Cathedral

1973 Frederik van Niekerk for Culpable Homicide for the Malmesbury Rail Disaster

1973 The Faros Coal Enquiry to investigate government contracts for the transport of coal

1975 The Appeal of ‘Scissors’ Murderess Marlene Lehnberg

1975 Six members of SWAPO for the assassination of Chief Philemon Elifas

1976 Steve Biko for defeating or obstructing justice

1976 David and Susan Rabkin for inciting and committing acts to promote banned organisations

1979 The Bethal Treason Trial of Zephania Mothopeng and 17 other Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) members

1980 Abdullah Naker for dealing in prohibited dependence producing drugs

1983 Johannes Theron for the murder of ex-Senator Dr Andries Visser

1984 SASOL Ltd, Strategic Fuel Fund and Helge Storch Nielsen for unpaid commissions

1987 Dimitrios Skoularikus for the murder of Alphons Tampa and Mr & Mrs Costas Phakos

He also represented the families of a number of people who died inexplicably whilst in police detention. These inquests allowed the families and the public to learn some of the bizarre circumstances surrounding the deaths of their loved ones at the hands of the Security Police.

1970 Imam Abdullah Haron, a 45 years old respected Muslim cleric and leader, was detained under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act on 28 May, 1969 and held incommunicado for 123 days until his death from on 27 September 1969 in the Maitland police station cells in Cape Town. The police claimed that it was from falling down a flight of stairs but the autopsy recorded 27 bruises one of which was 20x8cm. He also had a broken rib. The magistrate found to have died of a myocardial ischemia as the result of a dislodged blood clot and that “A substantial part of the said trauma was caused by an accidental fall down a flight of stone stairs. On the available evidence I am unable to determine how the balance (of injuries) was caused.”[2]

1976 Mapetla Mohapi a leader of the Black Consciousness Movement was arrested under the Terrorism Act on 15 July 1976 and was found dead in his cell at the Kei Road police station on 5 August hanging by a pair of jeans in a cell at Brighton Beach police station. The police claimed he had committed suicide.

1976 George Botha, a 30-year old teacher at Paterson High School, Port Elizabeth, was detained on 10 December under Section 22 of the General Laws Amendment Act. Five days later, he was dead at the infamous Sanlam Building which housed the Head Quarters of the Security Police in Port Elizabeth. The police claimed he had jumped down a stairwell from the 6th floor of the building.

1978 Dr. Hoosen Haffajee, a young dentist 26 years old, was arrested under the Terrorism Act on 3 August 1977 for being in possession of “subversive documents”. He was found in his cell less than 24 hours later hanging from his trousers. Again the Security Police claimed suicide and the pathologists report found that his death was consistent with hanging but it also noted that he had some 60 wounds on his body including his back, knees, arms and head.

1978 Lungile Tabalaza was 19 years old and was arrested for incidents of arson, robbery and the burning of a delivery vehicle. He was detained on 10 July and died the same day at the Head Quarters of the Security Police, in Port Elizabeth. The police claimed he had jumped from an unbarred window on the 5th floor of the building.

1978 Michael Heshu was beaten and then shot dead by police on 28 December 1977 in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth. He had been at a party with his girlfriend and on their way home they were stopped by the police and he was ordered to have sex in the street with his girlfriend. He refused. The police told his family that he had been killed by riot police during at attack on police. He had been shot three times and had a broken femur.

Sadly in all instances the magistrates chose to overlook the numerous bruises and injuries of the victims and found no one responsible for the deaths contributing to a “…culture of impunity in the SAP” [3] at the time.

He also acted on other matters on behalf of political prisoners and members of the African National Congress (ANC) such as Dullah Omar[4] , who he had lectured on Evidence in 1956 and 1957 and had known through his great friend and colleague at the Cape bar Advocate [5] , Albie Sachs and Jeremy Cronin.

After two acting appointments as a judge, the first in July 1988, Wilfrid Cooper was appointed to the Eastern Cape Bench in 1 March 1989 and then transferred to the Western Cape in 1991 where he remained until his retirement due to poor health in January 1998.

Judge Cooper’s health severely deteriorated, and after his wife’s death in June 2001, he moved into frail care at a retirement village Clé Du Cap in Kirstenhof, Cape Town where he died of a heart attack on the morning of 4 March 2004.

Judge Cooper had a great number of friends with diverse interests which included the acclaimed writer and academic, Prof. Etienne van Heerden. They were both interested in literature and law as Prof van Heerden had studied an LLB and qualified as a lawyer before turning to literature and writing. They would talk endlessly on Judge Cooper’s favourite writer James Joyce, and other writers, and historians. Prof van Heerden had the following to say of him:

“He loved life, had abundant energy and we had great times. When I moved to UCT from Rhodes, we saw less of each other; his health wasn't good and I also had setbacks and surgery, which meant that our party lives were over. I often had tea with him in his chambers in Queen Vic Street after I paid a visit to my publishers in the Waalburg Building close by and he liked to tell me of the inner workings of the system, and his worries about slipping standards and ignored conventions.

We spoke on the phone at least once a week, as he was a truly loyal friend who always kept regular contact.

It was clear that he worked hard, as the son of an engine driver on the platteland, to become a judge, a respected academic, and a great conversationalist. In many ways he would break the bonds of formality and snobbery, of language barriers and distance – and that was what I greatly liked about him. His world had little boundaries in that sense.”

Judge Cooper loved to socialise and intellectualise on any level; from the Owl Club which he joined in November 1955 and regularly attended their meetings for over forty five years, accompanying Gertrude, as social editor of the Cape Times, to attend socials events around Cape Town or a braai at home or with the farmers he befriended over the years in the Western Cape.

He enjoyed the outdoors and was a golfer at one stage but he had a love for the Karoo, Kalahari and Namibia where he would hunt from time to time with friends, farmers and colleagues and enjoy the open expanses and the harsh beauty. He was however not a particularly good shot so his favourite saying of his hunting was “Ek skiet swak maar jag lekker” as it was the company and talk around the camp fire that he particularly enjoyed. He also tried his hand at game fishing in False Bay from the boat of Simonstown attorney Vic Cohen when tuna still entered the bay from the deep sea in great numbers. His regular escape from his work, however, was to walk for many hours with the family dogs from Constantia Nek to Newlands Forest.

Judge Cooper and Gertrude have three children: two daughters, Susan-Ann and Megan, who were educated at Rustenberg Girls High School, and a son, Gavin, who attended the Diocesan College (Bishops). The eldest, Susan-Ann, graduated from the University of Cape Town and completed her studies in Canada where she is a lecturer in English literature in Ottawa; Megan after schooling studied the restoration of documents and manuscripts at the Camberwell College of Art in London and works at Windsor Castle as a member of the Queen’s Household staff where her expertise is used to conserve documents for the Royal Family. Gavin, after his schooling and two years national service, went into the world of commerce, and, having accumulated over thirty years experience, has owned and operated two businesses in international freight forwarding and customs clearing.

Judge Cooper also had three grand children; Matthew, Petra and Edward.

Endnotes

[1] The school opened in 1745 for girls and boys, in 1894 two separate schools were established, namely “Girls School” and “Jongens Publieke School” and in 1912 it became “Die Hoer Jongenskool”. In 1944 the girls and boys amalgamated again with the name “Hoerskool Swartland”.↵

[2] Cape Times, Wednesday, 11 March 1970↵

[3] The O’Malley Archives, Chapter 2, Regional Profile Eastern Cape↵

[4] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/dullah-mohamed-omar↵

[5] http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/benjamin-magson-kies-political-a...↵

Map showing Andhra Pradesh in Southeast India. Source:

Map showing Andhra Pradesh in Southeast India. Source:  Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi  Dr. Enuga Reddy, former Principal Secretary of the UN Special Committee against Apartheid.

Dr. Enuga Reddy, former Principal Secretary of the UN Special Committee against Apartheid.

Ahmed Kathrada, shot taken by the police during the Liliesleaf raid. Source: South African National Archives

Ahmed Kathrada, shot taken by the police during the Liliesleaf raid. Source: South African National Archives

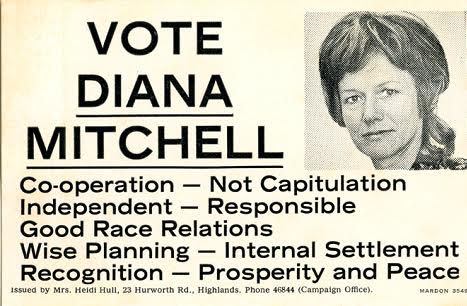

Voting poster for 1974 elections

Voting poster for 1974 elections  Diana Mitchell and her brother David in 1979

Diana Mitchell and her brother David in 1979